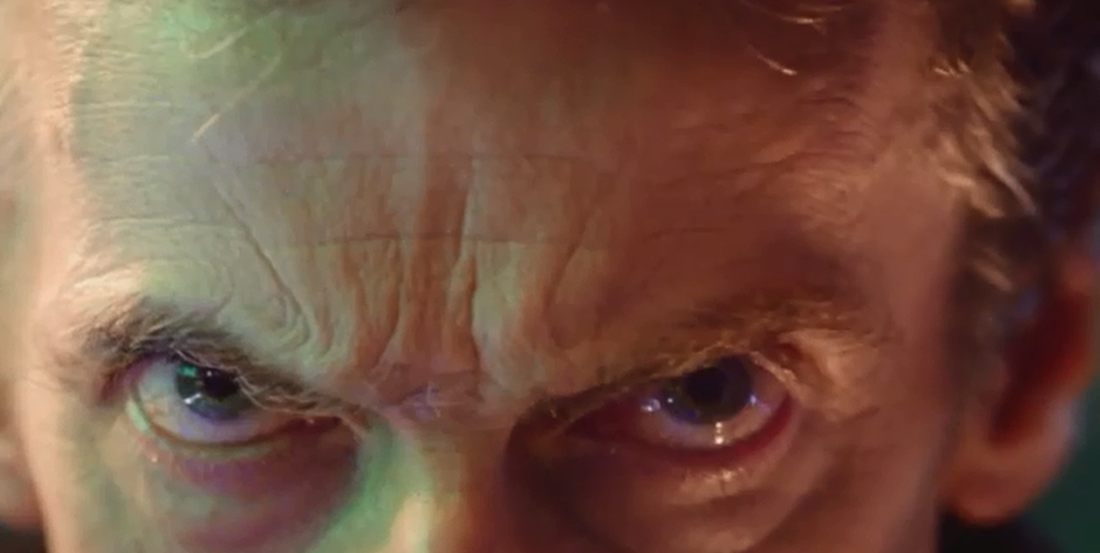

A few days ago I posted on Twitter a quotation from Doctor Who in response to the attacks on Paris. It was referring to the fact that wars are started with no knowledge of the individuals who will be hurt or killed by their actions:

“When you fire that first shot, no matter how right you feel, you have no idea who’s going to die.”

It is since that post that I have come to realise how many people on social media feel the necessity to express outrage, not at the indiscriminate acts of violence that tragically blight our lives, but at the way in which normal individuals show solidarity with the victims.

This made me wonder about a kind of moral pecking order that we seem to have created, a scale of righteousness that the average man on the street (the type who probably changed their Facebook profile picture to reflect the French Tricolore) has yet to climb. Peter Harness and Stephen Moffat – the writers of the episode from which the quotation was taken - must be viewed as some kind of hideous anti-moralistic monsters to have even suggested such simplistic anti-war themes within a family television programme. Whatever will we be indoctrinating our children with next? Liberty? Equality? Fraternity?

Recently I wrote about the versatility of science fiction; that it spans every human emotion without the constraints of reality. What it does as well, though, is to encapsulate and verbalise feelings that might otherwise be too immense to consider in the light of real life catastrophe.

Classic literature and poetry have always provided an insight into our innermost feelings, it is one of the most effective ways to access those parts of ourselves that most of us have no other means to reach; it is the purpose of art at its core. And times change; television, film, social media have joined the rich diversity of creative expression available and, in particular, open up new pathways for younger generations.

Wilfred Owen’s Futility, for me, resonated as I learnt the lines at school, naïve and idealist as most teenagers are. Should it matter from where I draw my inspiration to empathise, to help me to connect, to understand?

Move him into the sun--

Gently its touch awoke him once,

At home, whispering of fields unsown.

Always it awoke him, even in France,

Until this morning and this snow.

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.

Think how it wakes the seeds--

Woke, once, the clays of a cold star.

Are limbs so dear-achieved, are sides

Full-nerved,--still warm,--too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth's sleep at all?

Now I teach ten and eleven year olds and we inevitably discuss the news of the day and what it means to them and the impact it has on their lives. What better way to begin to understand recent events than to relate them to something the children know? To use popular culture does not diminish what has happened, rather it provides a wider range of people with a deeper appreciation of what has happened, in particular those people who are most likely to be making the decisions that will affect all of our futures.

So I stand by my post if it touches another human being and provides them with a way in.

You don’t know whose children are going to scream and burn, how many hearts will be broken, how many lives shattered.”

Such sentiments remain the same, whatever the media through which they touch our hearts.

“How much blood will spill until everyone does what they were always going to have to do from the very beginning: sit down and talk?”

Who can argue with that?

“When you fire that first shot, no matter how right you feel, you have no idea who’s going to die.”

It is since that post that I have come to realise how many people on social media feel the necessity to express outrage, not at the indiscriminate acts of violence that tragically blight our lives, but at the way in which normal individuals show solidarity with the victims.

This made me wonder about a kind of moral pecking order that we seem to have created, a scale of righteousness that the average man on the street (the type who probably changed their Facebook profile picture to reflect the French Tricolore) has yet to climb. Peter Harness and Stephen Moffat – the writers of the episode from which the quotation was taken - must be viewed as some kind of hideous anti-moralistic monsters to have even suggested such simplistic anti-war themes within a family television programme. Whatever will we be indoctrinating our children with next? Liberty? Equality? Fraternity?

Recently I wrote about the versatility of science fiction; that it spans every human emotion without the constraints of reality. What it does as well, though, is to encapsulate and verbalise feelings that might otherwise be too immense to consider in the light of real life catastrophe.

Classic literature and poetry have always provided an insight into our innermost feelings, it is one of the most effective ways to access those parts of ourselves that most of us have no other means to reach; it is the purpose of art at its core. And times change; television, film, social media have joined the rich diversity of creative expression available and, in particular, open up new pathways for younger generations.

Wilfred Owen’s Futility, for me, resonated as I learnt the lines at school, naïve and idealist as most teenagers are. Should it matter from where I draw my inspiration to empathise, to help me to connect, to understand?

Move him into the sun--

Gently its touch awoke him once,

At home, whispering of fields unsown.

Always it awoke him, even in France,

Until this morning and this snow.

If anything might rouse him now

The kind old sun will know.

Think how it wakes the seeds--

Woke, once, the clays of a cold star.

Are limbs so dear-achieved, are sides

Full-nerved,--still warm,--too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

O what made fatuous sunbeams toil

To break earth's sleep at all?

Now I teach ten and eleven year olds and we inevitably discuss the news of the day and what it means to them and the impact it has on their lives. What better way to begin to understand recent events than to relate them to something the children know? To use popular culture does not diminish what has happened, rather it provides a wider range of people with a deeper appreciation of what has happened, in particular those people who are most likely to be making the decisions that will affect all of our futures.

So I stand by my post if it touches another human being and provides them with a way in.

You don’t know whose children are going to scream and burn, how many hearts will be broken, how many lives shattered.”

Such sentiments remain the same, whatever the media through which they touch our hearts.

“How much blood will spill until everyone does what they were always going to have to do from the very beginning: sit down and talk?”

Who can argue with that?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed